Rival Photographer with Similar Style is not Copyright Infringer

Photographer Janine Gordon (“Gordon”) filed a lawsuit against rival art photographer Ryan McGinley (“McGinley”) claiming that McGinley infringed more than 150 of her photographs. Gordon also sued three galleries that exhibited McGinley’s works and Levi Strauss & Co., which used certain of the McGinley photographs in advertising campaigns.

Gordon alleged in her complaint that McGinley’s photographs are substantially similar to hers and, in fact, represent a pattern of infringement.

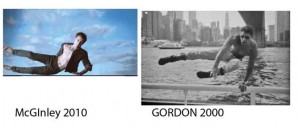

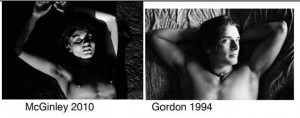

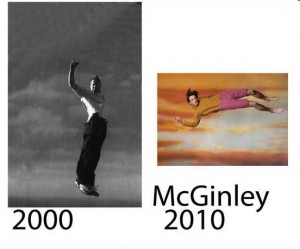

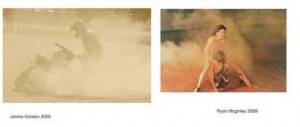

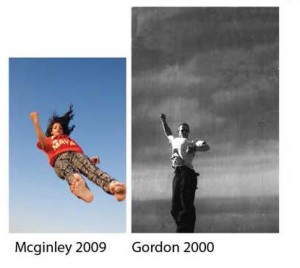

Side-by-side examples were dissected in detail by Gordon in the lawsuit. Above, below, and throughout this post are some of the examples Gordon used.

McGinley and the other defendants immediately moved to dismiss the lawsuit claiming that Gordon had not even set out a viable claim for relief in her complaint against the defendants. The defendants argued in their motion:

Plaintiff’s copyright infringement claims are frivolous and should be dismissed. Even a cursory comparison reveals that the McGinley Images are not substantially similar to protectable expression in the Gordon Images. In fact, the corresponding Images are vastly dissimilar and most of them do not look alike in the slightest. At most, they resemble each other in only the most superficial, abstract, and non-protectable ways. Plainly, however, plaintiff has no claim to ideas as general and unprotectable as, for example, an interracial couple kissing; a person gazing skyward with outstretched arms; or a man riding on a spotted horse.

Gordon countered by arguing that her images are not limited to basic unprotectable ideas, but rather are presented in a specific artistic manner which are protected by copyright.

[T]he Gordon Images do not express only the basic ideas inherent in their images. They are a rendition of Plaintiff’s mind’s eye, presented in a specific manner chosen by her to titillate, inspire and create discourse as to its meaning and her vision and intent. After all, “[i]t is not… the idea of a couple with eight small puppies seated on a bench that is protected, but rather Rogers’ expression of this idea–as caught in the placement, in the particular light, and in the expressions of the subjects . . . .” etc. (Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301). Plaintiff’s images were carefully selected by her as they occurred, and further manipulated to draw out other unique elements through the use of other elements used in its final rendition.

McGinley, however, requested that the court review the evidence presented by Gordon and dismiss the complaint, “Because no rational jury could conclude that the McGinley Images are substantially similar to the Gordon Images …”

McGinley argued that there is no direct copyright infringement, leaving only the issue as to whether the photographs are “substantial similar” enough to rise to the level of copyright infringement. To make this determination, the court must apply “the ordinary observer test, in which the Court must attempt to extract the unprotectable elements from consideration and ask whether the protectable elements, standing alone, are substantially similar.” (Psihoyos v. Nat’l Geographic Soc’y, 409 F. Supp. 2d 268, 274 (S.D.N.Y. 2005).)

In the court’s order granting the defendants’ motion to dismiss, the court first set the allegations against that McGinley exhibited a pattern of infringement.

The Complaint alleges a sprawling history of “surreptitious[]” copyright infringement (id. ¶ 2), in which McGinley obtained access to Plaintiff’s work through her public exhibitions (id. ¶¶ 48, 53) and thereafter produced “strikingly similar” images (id. ¶ 57). McGinley allegedly created images that were “both blatantly and subtly derivative” of Plaintiff’s work (id. ¶ 68) for a series of advertising campaigns commissioned by Defendant Levi Strauss (id. ¶ 66).

The court, then set out the basic test for copyright infringement.

In order to establish a copyright infringement claim, “a plaintiff with a valid copyright must demonstrate that: (1) the defendant has actually copied the plaintiff’s work; and (2) the copying is illegal because a substantial similarity exists between the defendant’s work and the protectable elements of plaintiff’s [work].” Hamil Am., Inc. v. GFI, 193 F.3d 92, 99 (2d Cir. 1999)

As to the second test, “substantial similarly,” the court explained that the test involves simply how an ordinary lay observer would view the two photographs side by side.

The standard test for substantial similarity between two items is whether an ‘ordinary observer, unless he set out to detect the disparities, would be disposed to overlook them, and regard [the] aesthetic appeal as the same.'” Yurman Design, Inc. v. PAJ, Inc., 262 F.3d 101, 111 (2d Cir. 2001) (quoting Hamil Am., 193 F.3d at 100). In applying the so-called “ordinary observer test,” the district court asks whether “an average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as having been appropriated from the copyrighted work.” Knitwaves, Inc. v. Lollytogs Ltd., 71 F.3d 996, 1002 (2d Cir. 1995). When faced with works “that have both protectible and unprotectable elements,” however, the analysis must be “more discerning.” Gaito, 602 F.3d at 66. In such circumstances, the district court “must attempt to extract the unprotectable elements from [its] consideration and ask whether the protectible elements, standing alone, are substantially similar.” Knitwaves, 71 F.3d at 1002 (emphasis omitted).

The court reviewed the photographs using this test and determined there was no reason to allow this case to move forward.

In this case, the dictates of good eyes and common sense lead inexorably to the conclusion that there is no substantial similarity between Plaintiff’s works and the allegedly infringing compositions of McGinley.

The fact that McGinley’s works may be ultimately derivative and unoriginal in an artistic sense – something which the Court has neither the expertise nor inclination to pronounce upon is beside the point. Most commercial advertising is derivative in that sense, and as the Second Circuit has observed, “not all copying results in copyright infringement.” Boisson v. Ban ian, Ltd., 273 F.3d 262, 268 (2d Cir. 2001).

The court pointed out that Gordon is essentially asserting a copyright interest in every photograph of with outstretched arms. (Certainly the first photo of a person with their arms up on the air was not taken by Gordon in the 1990’s. I am sure I can find a childhood photo of myself jumping up in the air in the 1970’s). The court then goes on to scold plaintiff’s attorneys for wasting everyone’s time with this case.

Plaintiff’s apparent theory of infringement would assert copyright interests in virtually any figure with outstretched arms, any interracial kiss, or any nude female torso. Such a conception of copyright law has no basis in statute, case law, or common sense, and its application would serve to undermine rather than promote the most basic forms of artistic expression.

One might have hoped that Plaintiff – an artist – would have understood as much, or that her attorneys, presumably familiar with the basic tenets of copyright and intellectual property law, would have recognized the futility of this action before embarking on a long, costly, and ultimately wasteful course of litigation in a court of law. In any event, for the reasons set forth above, and as should have been obvious from the outset, the Court grants the motion to dismiss Plaintiffs copyright infringement claim.

The court thus ordered that the plaintiff’s complaint should be immediately dismissed.

Because Plaintiff has failed to meet even the most basic threshold for pleading copyright infringement, Defendants’ motion is granted.

It is not known whether the plaintiff plans to appeal this ruling.

About Me

Recent Posts

- Dash v. Floyd Mayweather: Copyright Damages Require more than mere Speculation

- Copyright Renewal Rights Must be Transferred with Specificity

- Mobile Phone Carriers not Indirectly Liable for Text Message Copyright Infringement

- Can you get Copyright Protection on an Informational Diagram?

- WNET v. Aereo: Is renting a TV antenna copyright infringement?