Blehm v. Jacobs: Can you Infringe the Copyright of a Stick Figure?

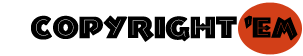

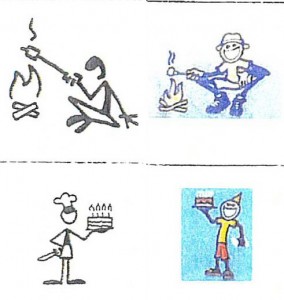

Plaintiff Gary Blehm is the creator of series of stick figures named “Penmen” (pictured on the left). The defendants, Albert and John Jacobs, created their own series of stick figures named “Jake” (pictured on the right).

Blehm developed the Penmen characters in the 1980’s and had several posters of the Penmen characters copyrighted. Around 1994 defendant John Jacobs first drew Jake. Initially Jake was just a head, but later a body was added to Jake along with the slogan “Life is good.”

Coincidentally (or intentionally according to the plaintiff) Jake was placed in a number of poses and activities strikingly similar to the Penmen. Blehm identified sixty-seven Jake images that were very similar to Penmen images. Perhaps there are only so many poses and activities a stick figure can do, but the resemblance between some of the images is uncanny.

While it appears that the defendants are “copiers” are they “infringers”? Is the idea of putting a stick figure into various poses and activities protectable?

“In order to prove copying of legally [protectable] material, a plaintiff must typically show substantial similarity between legally [protectable] elements of the original work and the allegedly infringing work.” Jacobsen, 287 F.3d at 942-43. This commonly stated rule raises two questions: First, what elements of a copyrighted work are legally protectable? Second, how do courts determine whether a copyrighted work’s legally protectable elements are “substantially similar” to an accused work?

Copyright protects original works of authorship with a minimal degree of creativity. But not all elements of a copyrighted work are protectable.

Section 102(b) provides, “In no case does copyright protection . . . extend to any idea . . . [or] concept . . . regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(b). This provision enshrines the “fundamental tenet” that copyright “protection extends only to the author’s original expression and not to the ideas embodied in that expression.” Gates Rubber Co., 9 F.3d at 836; see also Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters., 471 U.S. 539, 547 (1985) (explaining that copyright protection extends only to “those aspects of the work—termed ‘expression’—that display the stamp of the [plaintiff’s] originality”); Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301, 308 (2d Cir. 1992) (“[I]n looking at . . . two works of art to determine whether they are substantially similar, focus must be on the similarity of the expression of an idea or fact, not on the similarity of the facts, ideas or concepts themselves.”).

Here, the Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit held that Penmen and Jake are not substantially similar. Moreover, the similarities between the two sets of stick figures (i.e. the poses and activities) not protectable under copyright.

Copying alone is not infringement. The infringement determination depends on what is copied. Assuming Life is Good copied Penmen images when it produced Jake images, our substantial similarity analysis shows it copied ideas rather than expression, which would make Life is Good a copier but not an infringer under copyright law.

The idea of a stick figure giving a peace sign and the idea of a stick figure catching a Frisbee is simply not protectable creative expression. So while it appears that the defendants copied the plaintiff, they infringed ideas and themes rather than protectable expression. And so the court ruled in favor of the defendants, and life was good for them.

About Me

Recent Posts

- Dash v. Floyd Mayweather: Copyright Damages Require more than mere Speculation

- Copyright Renewal Rights Must be Transferred with Specificity

- Mobile Phone Carriers not Indirectly Liable for Text Message Copyright Infringement

- Can you get Copyright Protection on an Informational Diagram?

- WNET v. Aereo: Is renting a TV antenna copyright infringement?