Can you get Copyright Protection on an Informational Diagram?

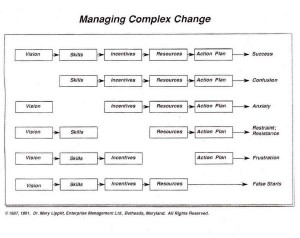

Plaintiff Enterprise Management Limited holds copyrights for the following diagram:

Defendant Donald W. Warrick, who teaches in the organizational development field, copied the diagram and incorporated it in his course materials after receiving a copy from a student. At the trial court, Warrick moved for summary judgment arguing that the diagram was not entitled to copyright protection. The trial court granted the motion and dismissed the case. The Plaintiff appealed.

Warrick argues that Plaintiff’s diagram is not entitled to copyright protection as it lacks the request creativity to merit copyright protection and consists primarily of “ideas, concepts, principles or discoveries” that are not copyrightable. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed. The court held that because there are many different ways to express the facts and ideas expressed in the diagram, the diagram itself is a creative work entitled to copyright protection.

Warrick argues Lippitt’s diagram is not eligible for copyright protection because it consists only of unprotectable ideas or expression so intertwined with the underlying ideas as to lose their protection under the merger doctrine. In Warrick’s view, Lippitt’s diagram expresses a “fundamental” idea about organizational change and development. (Answer Br. 25.) It is, he says, a “statement about objective reality, not a work of fiction or the imagination.” (Id.)

Warrick misses the point. Although Lippitt’s diagram may express an idea, Warrick could express the same ideas in his own fashion. He might have organized the components in a pie-chart-style format to show how each is a component of a larger whole. He could have approached the concept in a two-column format, listing each defect in the left column and the missing component in the right column. He could have simply described the concepts in prose, as he did in his motion for summary judgment. He could have used his own words to describe the components. He might have broken down or combined the components in a different way. He could have expressed the absence of one of the components with an “X” over the component, as did another writer’s sample diagram; one Lippitt attached as Exhibit 10 to her response to Warrick’s summary judgment motion. (Appellant’s App’x 247-52.)

Defendant Warrick further argues that the elements of the diagram are not sufficient for copyright protection.

Warrick says the elements of Lippitt’s diagram—short labels, shapes, symbols, and selection of typeface— are not eligible for copyright protection. See Arica Inst., 970 F.2d at 1072-73 (noting individual words and short phrases are generally not copyrightable); Atari Games Corp. v. Oman, 979 F.2d 242, 247 (D.C. Cir. 1992) (noting “simple geometric shapes and coloring alone are per se not copyrightable”) (quotations omitted); 37 C.F.R. § 202.1(a) (“familiar symbols” and “mere variations of typographic ornamentation” are not copyrightable). In essence, Warrick claims the diagram lacks the “minimal degree of creativity” necessary to qualify for copyright protection, even though “the requisite level of creativity is extremely low.” Feist Publ’ns, 499 U.S. at 345; see CMM Cable Rep, Inc. v. Ocean Coast Props., Inc., 97 F.3d 1504, 1519 (1st Cir. 1996) (listing examples of expression lacking the requisite creativity).

Again, the Tenth Circuit disagreed.

Warrick’s view misses the forest for the trees. Any copyrightable work can be sliced into elements unworthy of copyright protection. See CMM Cable Rep, 97 F.3d at 1514. Books could be reduced to a collection of non-copyrightable words. Music could be distilled into a series of non-copyrightable rhythmic tones. A painting could be viewed as a composition of unprotectable colors. Warrick’s impulse to unpack Lippitt’s diagram into ever-smaller and less-protectable elements is understandable, as copyright jurisprudence tends toward dissection.

Nevertheless, a limiting principle constrains this reductionism. We must focus on whether Lippitt has “selected, coordinated, and arranged” the elements of her diagram in an original way. Feist Publ’ns, 499 U.S. at 358; Knitwaves, Inc. v. Lollytogs Ltd., 71 F.3d 996, 1004 (2d Cir. 1995); see also Feist Publ’ns, 499 U.S. at 349 (“[I]f the selection and arrangement are original, these elements of the work are eligible for copyright protection.”).

The Appeals Court reversed the trial court’s grant of summary judgment and remanded the case where it will proceed with discovery and then on to a trial on the merits.

About Me

Recent Posts

- Dash v. Floyd Mayweather: Copyright Damages Require more than mere Speculation

- Copyright Renewal Rights Must be Transferred with Specificity

- Mobile Phone Carriers not Indirectly Liable for Text Message Copyright Infringement

- Can you get Copyright Protection on an Informational Diagram?

- WNET v. Aereo: Is renting a TV antenna copyright infringement?